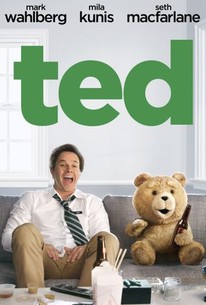

Another comedy based on the principle that the American male is nothing but a loveable man-child who can’t grow up. Here’s the interesting spin: as a child, he’s a little lonely and wished for his eponymous teddy-bear to come to life, which it did, and now Ted acts as his bad influence and represents his arrested development. This means the gags are based upon the bear making a stream of inappropriate wisecracks, simulating sex acts, organising hooker parties, being racist (because being obnoxious masquerades as being rebellious) and getting wasted. And learning about cocaine from Sam J. Jones (Flash Gordon himself). Much of this is quite funny and diverting but the film has no idea how to explore its potential and, in the manner of all comedies that run out of imagination, steers headlong into uninteresting thriller mode in the last act to try and provoke unearned sentiment. The whole bear-in-peril plot might have worked up something genuinely satirical – since Ted is a faded celebrity – in a kind of “King of Comedy” manner, but for all its pop-culture references and profanities, it really is very conventional and somewhat ultimately dull because of it.

"Nothing bothers some people. Not even flying saucers." - The Beast of Yucca Flats

Tuesday, 27 February 2018

Friday, 23 February 2018

The 'Evil Dead' trilogy

EVIL DEAD

Sam Raimi, 1981, USA

EVIL DEAD II

Sam Raimi, 1987, USA

ARMY OF DARKNESS

Sam Raimi, 1992, USA

When I was a kid, the TV spots advertising ‘The Evil Dead’ terrified me. That witchy-demon banging around and glaring up from the cellar truly intimidated me, enough that I had to steel myself every time the commercial ran.

1981: Seemingly armed with nothing but a cabin in the woods and a smoke machine, Sam Raimi used these to try out his technical gusto and to make horror history. Ash (Bruce Campbell) and friends go to the isolated cabin to get away but find themselves at the mercy of demons with a pretty slapstick sense of things. Although the comedy and the Cult of Ash would take over, there is a d.i.y. and transgressive edge that feels rooted in Seventies exploitation cinema so that those features, at this stage, remain sly gags. Details such as the mirror that turns to water edges into the kind of surrealism that ‘Phantasm’ excelled in (but it’s true that the Book of the Dead looks like something your Heavy Metal mate might have drawn in a school text book). There’s plenty of invention and detail all round – in using a pencil for a demonic assault and blood giving a projector a red filter, for example – to show how Raimi’s debut earned its reputation. It may seem ridiculous now to think a horror so obviously influenced by cartoons and slapstick could spearhead the “Video Nasty” phenomenon, but there is the wrong-headed tree rape and a genuine sense of the unhinged to indicate how people that didn’t understand the genre would be outraged. That, and enough splatter, dismemberment and stop-motion to really push things as far as they can go. And the camera hurtling through the trees as a demonic force still remains a simple but unforgettable horror technique. The tree-rape is an unnecessary misstep, though and the whole thing just narrowly misses a subtext of fratboys-take-girls-to-cabin-and-the-girls-are-nuts! There’s an overall gonzo humour that somehow circumnavigates anything just being offensive. Even when you are clued in to its full throttle rhythm, there’s a pause and stillness to the stop-animation at the end (probably the only notable stillness in the film) that taps into genuine eeriness. Very few films feel this kinetic, like a sloppily aimed punch, and despite its gleeful pell-mell liquefying into outré slapstick, it still holds onto something intrinsically scary, unnerving, bizarre and outrageous.

‘Evil Dead 2’ (1987) is a rewrite of the original as a more straightforward comedy of madness. The use of green blood is always telltale sign of compromise but even so, this sequel is the equal to the original in breakneck invention and punk-brat fuck it! agenda. This is how you revisit/reboot/remake an original (rather than Fede’s Alvarez’s 2013 bland/terrible ‘Evil Dead’). There’s a place where bad dialogue and so-so acting won’t matter, and this is it. Bruce Campbell is admirably game and mugs his way dementedly through it all with verve to match the film-making as it just heaps more and more upon him. Perhaps the bigger budget means it’s descent into giant demon heads is unavoidable, but the first half especially excels at depicting one man’s elevation into insanity through cartoon excess. Apparently all this was in lieu of Raimi’s original intention of a

medieval dead which the budget couldn’t stretch too – which we get to next – but there is no disappointment in this sequel just regurgitating more of the original. We know the tricks but Raimi shows he can pull it out of the hat a second time with no problem, showing the original was not a fluke.

And so time-travelling we go: ‘Army of Darkness’ (1992) is fully defined by the Cult of Ash and makes ‘Evil Dead’ a joke. I mean that both as summary and detrimentally. Apparently this is what Raimi had intended all along with the concept, but now he had the cash to do it. The “Deadites” hold no mystery or disturbing qualities here, although there is fun to be had in their designs. If the original brashly held the coat-tails of slapstick and horror and the sequel still maintained fidelity to this, this third installment is some weird Harryhausen tribute mixed with satirical macho posturing. This is nothing like a continuation from the Ash from the first two films: he wasn’t much of a character but he was sympathetic and put upon and we could relate to his descent into insanity. The constant Bruce Campbell-bashing was a fun in-joke; he is charismatic without having to do much. But ever since he uttered “Groovy!” it’s been a descent to what he is here: a privileged wisecracking asshole who’s supposed to be funny because of it. It’s that thing where his overt machismo is at once parodic and

wallowing in itself. “Gimme some sugar!” and so on, you can quote later. But his wisecracks aren’t funny (your-mileage-may-vary) and it coasts on the Bruce Campbell mythology which has now taken hold – here’s a mini-Ash army; here’s his demonic double – and it isn’t scary or unnerving at all. Of course, it isn't meant to be: it's a romp. It holds some weight as Ash’s narcissistic manic nightmare, but it’s also caricature over character. There are times when it feels decidedly amateurish, badly lit and juvenile, and perhaps it has the same zest of its predecessors but the invention here seems self-indulgent. Luckily, there was plenty more good stuff to come from Raimi.

Labels:

comedy,

demons and devils,

exploitation,

fantasy,

horror,

sequels,

Video Nasties

Wednesday, 14 February 2018

Blade Runner 2049 - a second watch

Watching ‘Blade Runner 2049’ again, it seems to me that the accusations of a too-slim narrative are misguided: every scene is full of theme and the revelation of plot details that texture and drive the narrative. But, yes, the visuals are so immersive that the superficial reaction is that they are dominant; the tone is a little abstract and underplayed so that it is perhaps easy to miss the details of narrative being disclosed through hints and dialogue.

For example, the human-free showdown that opens the film sets up a replicant-killing-replicant backdrop: Ryan Gosling’s slightly regretful but unquestioning execution of his programming; Dave Bautista is living a solitary existence hiding away on a farm until Gosling tracks him down; these are artificial humans that debate briefly how to resolve the situation before Bautista calls out K/Joe/Gosling’s motivation, saying how it’s because he hasn’t seen a miracle. This sets up the key theme of artificial humans always trying to be human. Later, it will be suggested that Bautista let himself be killed to protect the secret of the human-replicant birth, retrospectively giving this moment an extra theme of self-sacrifice as well as playing into the philosophy that to die for a cause is the ultimate human behaviour. This leads to Gosling discovering the bones of a body that triggers the story of the replicant-human baby that drives the plot. There seems to me here plenty to chew on during the set-up, providing not only crowd-pleasing visuals and a fight, but setting up motivation and themes that thread and are coloured in throughout the film.

And then there is the thorny issue of gender politics, but it seems obvious that almost every male character is confused or/and weakened or/and deluded whereas all the female characters are mostly certain and clear and direct. It is the women that are the true power in ‘Blade Runner 2049’, no matter how much the culture’s veneer of misogyny insists otherwise. Even with Joi, Gosling’s stay-at-home fantasy “wife”, she seems to enact her programmed devotion to Joe with individualist determination and invention. She is not passive although she may be deferential. It seems Joe’s fantasy is to have a loyal woman who takes charge and reassures him as much as she serves holograms of better food. This surely indicates his insecure nature… but that surely can’t be his programme? Even with the replicant prostitute we see hints of individualism if not independence (but movie prostitutes are typically feisty, it’s true). Later, he will see Joi advertised through sexual promise, coded in vibrant pink, but it is not so clear if this shatters his illusion of her or simply reinforces her differences to him. This is the most tender and humane relationship in the film and it’s the interplay between false humans. There is nothing we can read as un-human or unusual in their communication as we might the conflict of Luv (Sylvia Hoeks) crying as she kills. Where the rise of technology tries to make everything as human and interactive as possible through means of nostalgia, ‘Blade Runner 2049’ offers a decent vision of a future resulting from this conflict. It’s a future where artificial humans develop identity crisis and seek solace in holograms. Technology so far gone it has to reassure itself. It barely needs humans at all. It’s a future that arguably insists on the misogynistic culture that guided Ridley’s original – itself derived from film noir – even as the evidence of the real world negates it.

And then there's the symbolism of rebirth in the waves although the more obviously religious is commendably avoided.

And then there's the symbolism of rebirth in the waves although the more obviously religious is commendably avoided.

These are just a couple of ruminations of many inspired by a second watch of ‘Blade Runner 2049’, and there are sure to be more with repeat viewings. Each scene is vibrant with these themes and questions into identity and motivation. Like the original, it’s an experience that rewards and becomes more textured on repeat viewings. And again, it is surely an achievement that it gives answers whilst still maintaining much ambiguity. If nothing else, there is the glorious cinematography of Roger Deakins and the thunder and the synth tsunami of Hans Zimmer and Benjamin Wallfisch to overwhelm the senses. But there is depth beneath these pleasures.

Labels:

androids,

Blade Runner,

Dystopia,

future worlds,

robots,

science-fiction

Saturday, 10 February 2018

Brawl in Cell Block 99

S. Craig Zahler, 2017, USA

Bradley Thomas is having a bad day: he’s just been fired and goes home to discover his wife (Jennifer Carpenter) is cheating. He turns to drug-running to resolve issues, but this is not to imply he’s just a scumbag or weak-willed: rather, he’s just a pragmatist that does what he feels needs to be done. But he has the ultra-violence and savvy to back it up. Nevertheless, getting involved with bad people eventually only leads to more trouble and a descent to cell block 99 and there’ll be no more turning his back on a violent nature.

The cover blurb quotes The Hollywood News saying “The most impressive director since Quentin Tarantino,” but S. Craig Sahler has in Bradley Thomas a character that cuts through all the verbose digressions and bullshit to the bone – the kind that both Tarantino and Vaughn are known for. Vince Vaughn plays Bradley with less of the Clint Eastwood existential machismo or Charles Bronson’s disinterest, but rather like ‘Point Blank’s Lee Marvin striding in and just punching without fanfare. The only one that seems likely to veer into broad villainous caricature is Don Johnson’s Warden Tuggs, but that turns out to be something of a red herring, despite being a lot of fun.

Bradley Thomas is someone who appears to have mostly turned his back on a life of violence but he triumphs at it when he unleashes. Sahler’s previous film ‘Bone Tomahawk’ established that he excels at extreme violence (very few times have a felt an audience so physically reacting to a killing), and ‘Brawl’ doesn’t disappoint. There is bound to be one or two moments that will lodge into your memory as un-erasable once seen. If films like ‘The Villainess’ and ‘The Raid’ are about skill, this is about brute force and in keeping with that candour action is not conveyed through fast cuts but rather unflinching straightforward shots. It is Vaughn’s hulking physical and terrifying directness that is likely to be most memorable.

Bradley Thomas is someone who appears to have mostly turned his back on a life of violence but he triumphs at it when he unleashes. Sahler’s previous film ‘Bone Tomahawk’ established that he excels at extreme violence (very few times have a felt an audience so physically reacting to a killing), and ‘Brawl’ doesn’t disappoint. There is bound to be one or two moments that will lodge into your memory as un-erasable once seen. If films like ‘The Villainess’ and ‘The Raid’ are about skill, this is about brute force and in keeping with that candour action is not conveyed through fast cuts but rather unflinching straightforward shots. It is Vaughn’s hulking physical and terrifying directness that is likely to be most memorable. There’s nothing new in the narrative but it’s all executed with a slyly fated and doomed air as if this is more than just riffing on that exploitation staple of the super-violent man hammering vengeance on all and sundry. But it’s very much grindhouse brutality through arthouse melancholy, the latter somewhat shaving off the rough edges of the former, making it gratuitous and restrained at the same time. There is none of the thoughtfulness on the topic of violence and community here that ‘Bone Tomohawk’ offered – indeed it appears that this was written beforehand – but that’s probably moot when you are flinching/giggling at the excess. ‘Brawl in Cell Bock 9’ offers movie violence and a more-or-less unbeatable fantasy male in a probably never-better Vince Vaughn performance. It’s a straightforward guilty pleasure where Zahler’s pacing and skill subscribes to a sincerity beyond trash even as Udo Kier is talking about dismembering foetuses and heads are being stomped.

There’s nothing new in the narrative but it’s all executed with a slyly fated and doomed air as if this is more than just riffing on that exploitation staple of the super-violent man hammering vengeance on all and sundry. But it’s very much grindhouse brutality through arthouse melancholy, the latter somewhat shaving off the rough edges of the former, making it gratuitous and restrained at the same time. There is none of the thoughtfulness on the topic of violence and community here that ‘Bone Tomohawk’ offered – indeed it appears that this was written beforehand – but that’s probably moot when you are flinching/giggling at the excess. ‘Brawl in Cell Bock 9’ offers movie violence and a more-or-less unbeatable fantasy male in a probably never-better Vince Vaughn performance. It’s a straightforward guilty pleasure where Zahler’s pacing and skill subscribes to a sincerity beyond trash even as Udo Kier is talking about dismembering foetuses and heads are being stomped.

Labels:

action,

Bone Tomahawk,

crime thriller,

exploitation,

fight film

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)