Film Notes part 3: drama & thrillers

Aside from ‘Casino Royale’ – which I love and consider one of the best in action he-man cinema – and earlier instalments, James Bond doesn’t do so much for me, but it seemed fully appropriate to complete Daniel Craig’s Bond arc in ‘No Time to Die’ with the finale explosion. I thought Craig was good, but the urge to give backstory and introduce children seemed an unnecessary and a bad fit for this particular action-fantasy.

A film like Teodora Mihai’s ‘La Civil’ was

the kind of drama that shows up fantasy-action films for lacking the social

consequences the crime scenarios riff on.

Jonas Govaerts’s ‘H4Z4RD’ came from the more

lowlife end of crime fiction. Filmed totally from within a car, this is a fun

and furious thriller that is perhaps ultimately not a quite as goofy as

expected from the first half. One of those “One Bad Day” plots where the bad

luck just piles on for our petty-crime adjacent protagonist. He and his car

must take punishment upon humiliation until he learns his lesson (well, we can

assume he does).

The formal fun and pounding soundtrack and some off-colour gags make this entertaining, a memorable entry in the lowlife farce sub genre.

In David Victori’s ‘Cross the Line’, mild-Mannered

people-pleaser Dani (Mario Casas) has devoted his recent life to caring for his

father, but now it’s time to move on and start anew. And he’s on the verge when

he crosses paths with the kind of domineering good time girl that you know is

going to be trouble. The film makes exceptional use of music as it goes from

dad’s unremarkable dying room to neon nightmare as Dani finds that straying

from his caution only gets him deeper and deeper into trouble and desperation.

Victori is obviously going for something more poignant

here with the title (online translator says the original Spanish translate as

“You will not Kill”?), but the fun is following how things, pretty

realistically, spiral out of control, forcing increasingly desperate and

extreme reactions. Like ‘Victoria’, there’s a sense of playing out in

real-time across the city, the handheld camera staying close to the

protagonist– in this case, across Barcelona. It won’t win any friends with

portraying the threat as a wild side female, in film noir style or a nineties

“yuppie peril” scenario, but Smit’s performance is compelling. However, it’s

Casas’ portrayal of a man being altered for life by one night, the toll taken

showing increasingly on his face, that really grounds the film. Perhaps the

film ultimately overreaches for sadness rather than closure, but it’s a vivid

and entertaining thriller with lots of panache.

Adam Mackay’s ‘Don’t Look Up’ had a

pedigree cast and a satirical bent that was sharp enough to upset the right people

with a certain criticism of the mainstream media’s shallowness and callousness.

Perhaps I thought its targets were too obvious, but it captured a certain zeitgeist

with its focus on the venality and egos of politicians and media and the narcissism

of a tech-bro scuppering the survival of humanity. Applying a typically

American Mainstream bright-and-breezy gloss and a little sophistication to politics

– ref: ‘The Big Short’ – certainly helped reached a wide enough audience

to outrage.

Joachim Trier’s ‘The Worst Person in the World’ was

peppered with memorable moments (the flirtation at the party being a personal

favourite), this is a superior character study of fickleness and the roaming

intentions and disappointments that come with aging. Indecision about who you

are and where you are going lingering long after you’ve grown up is a theme not

widely pursued aside from the dominance of the Man Child in mainstream

entertainment, so it’s nice to see it dealt with such a mature eye here.

Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s ‘Drive My Car’ suffered

from taking a little overlong to reach its destination. The journey was

beautiful, understated and immaculately crafted, but coming to the last act you

may wonder if it will actually arrive anywhere. But it does, so all the beguiling

incidentals aren’t left hanging. It’s a mature film about the lingering and open-endedness

of grief and life, and knowing its destination, a second watch will no doubt be

an even more fulfilling journey.

Speaking of upsetting chillers: Justin Kurzel’s ‘Nitram’

scored high in its deceptively mater-of-fact rendering of the infamous Australian

mass shooting. Between this and "Snowtown", Justin Kurzel proves

again a master of the upsetting and grim, in capturing with empathy and a

relentlessly clear eye on pending national trauma. With stunning performances

by Caleb Landry Jones and Judie Davis, this again shows Kurzel's adeptness in

fleshing out characters that commit monstrous atrocities with empathy but not

endorsement (including ‘The True History of the Kelly Gang’).

In this portrayal of "Nitram" and the

build-up to the 1996 Port Arthur massacre, the frightening observation is of

someone that has no sense of the consequences of his actions, and of how

dangerous he is. Although one can sympathise with his ineptitude with social

skills and subsequent loneliness, this lack of self-awareness is terrifying. Although

not quite as relentlessly bleak as ‘Snowtown’, and on top of its anti-gun

polemic, the focus on issues of how to assimilate someone with problematic behaviour

and mental health issues was uncomfortably central.

Philip Barantini’s ‘Boiling Point’ delivered

one of the best portrayals of working life on screen, focusing on a single

night’s shift in a restaurant. It’s focus on the overlap of detail, on the

interplay of mini-dramas hardly aware of one another, struck a recognisable

truth to anyone familiar with a busy workplace. For this, it deployed a single take to capture

how drama and conflict unfolds in real time, giving this aesthetic a purpose that

surpassed its gimmick status (and I am a sucker for the choreography of the

one-take).

Alternatively, on the less neo-realistic side, there was Mark Mylod's 'The Menu'. Although you will go in knowing the nature of the beast, there's enough unpredictability to keep you at the table and the sprinkling of social commentary adds a little substance. Mostly, it's an enjoyable enough Mad Chef tale.

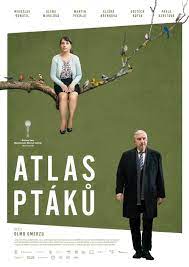

Olmo Omerzu’s ‘Bird Atlas’ provided a droll

family drama focused on a ruthless, selfish patriarch of a technology company.

He is an irredeemable aging bully and, when taken seriously ill, one son seems

to be making his move, the other is a quiet enabler, and the daughter is

preoccupied with a new baby. The trouble starts when company millions go

missing. Yes yes, a ‘Succession’ scenario, but less gaudy and acerbic

and the characters aren’t wholly obnoxious. In fact, there’s a straightforward

approach to mundane glass and vanilla set design that is akin to the drabness

of soap operas. But there is a bright trip to a snowbound apartment, and one

fantastic shot of a blue train going through a snow-white mountain route.

There’s weight when the unappealing Ivo – a stony Miroslav

Donutil – momentarily turns into an unlikely anti-hero detective to pursue the

mystery and money. Just when it verges on being too dry for its own good, to

almost tedium tedium, there’s a touch of the fantastical when birds, via

subtitles, start to give philosophical and business observations. And it’s a

tale where no one gets what they want and one man’s loveless attitude leaves a

trail of unhappiness. A moderate drama that occasionally hits real heights but

might be an underachiever. But the Greek Chorus of birds is inspired.

Ben Parker’s ‘Burial’ was perhaps minor,

but a decent World War II that I expected to be a vampire flick, maybe, for a

moment, but isn't. Rather, it's a solid wartime drama set in a horror landscape

- coffin, woods, shadow-monster and isolated taverns. The tone is suitably

austere but not drab and desperate, the performances good, the action decent

too if occasionally lost in the shadows.

But for the real wartime deal, there was Edward berger’s

‘All Quiet on the Western Front’. A German adaptation of

Erich Maria Remarque’s phenomenal novel which whilst marking key moments

deviates from the source is truer in spirit rather than detail. It is a truism

that war films are often remarkable and thrilling in spectacle, admirable and

awe-inspiring in technical achievement even as they depict the very worst human

kind has to offer (‘Come and See’ is as beautiful as it is traumatic,

for example), and this ‘All Quiet on the Western front’ is no different.

Its depiction of the trenches and the use of stunning

aerial shots, for example, are cinematically transcendent even as they glide

into the mud and corpses of the trenches and No Man’s land. It stays on the

front and forfeits the tale of soldiers returning home and being dissatisfied,

of no longer fitting in, so the final image of Paul finally finding peace is somewhat

lessened. This is replaced with a focus on the subplot of the politics, of men

trying to stop the war and of arrogant, warmongering higher-ups sacrificing

young men for their own ego and jingoism, a theme true to the novel. However,

Paul’s final intimate scuffle that pauses when both soldiers realise that they are

really just the same in their fatigue and horror, which is at odds with the

faceless slaughter on the battlefield, strikes a resonant chord.

Rightfully horrifying, pretty and brutal, nicely

performed and often stunningly filmed, an outstanding achievement.

For something joyful, if troubled: Panah Panahi’s ‘Hit

the Road’ is set against rugged Iranian terrain and powered by the

non-stop energy of child actor Rayan Sarlak, this slightly mysterious family

road movie seems minor and intimate but reaches deep. Superficially jubilant

and bright, but there’s desperation and persecution beneath. Nevertheless, the

family never the let the peril get in the way of family squabbles and age-old

grievances, so there’s almost a farcical edge. It’s bright, fizzing with

interplay and detail (starts with the kid drawing a keyboard on a leg cast),

amusing (the encounter with the cyclist is a highlight) and not adverse to a

little musical interlude to reach even further, achieving something

bittersweet.

And Martin McDonagh’s ‘The Banshees of Inisherin’

was his most satisfying since his debut. Maybe verging a little ‘Father Ted’

at times, but mostly this is a picturesque exploration of the heartbreak

that can enter male friendships and how those feelings manifest as bafflement,

bitterness, resentment and violence. Oh, and self-destruction. The women know

to get out when they can. Fine performances (is there no end to Barry Keoghan’s

utterly mesmerising disturbing-disturbed-sympathetic oddballs?), sparse

aesthetic, funny and increasingly dark and weighty.

No comments:

Post a Comment