Dune

Frank Herbert, 1965

Fortuitously, Villeneuve’s first part of adapting

Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’ finishes just at the point I had read up to in

the book at that time (halfway). The novel has sat in my “to read” pile since I

was a teenager smitten with science-fiction, and I have no idea why it has

taken a lifetime to get around to reading it. Perhaps I was intimidated by its

reputation as “difficult” and/or “dense”? Well, it is dense and uncompromising

and the world-building is exemplary, the kind I already knew from Jack Vance;

although Vance feels pulpier and Herbert more serious in intent. World building

is the genre’s chief pleasure and super-power. It’s enthralling and its place as

One Of The Best and Highly Influential is obvious and well earned. It is full

to bursting with detail, characters, culture and political intrigue and themes

without losing focus or reader.

Its themes are the grandest: the

intersecting of politics and religion and economics, cultures and war and guilds

and totalitarianisms, of mesiahs and their followers, etc. It is full of

snippets of wisdom dispensed in fake memoirs and political and religions tomes.

It is full of the mechanics of politics and schemes that often feel like the Machievelli’s

‘The Prince’, or Sun Tzu’s ‘The Art of War’. For example: How you

pay for military might? Make prison planets. And peppered with existential

wisdom such as, “How often it is that the angry man rages denial of what his

inner self is telling him.” Or, “the real universe is always one step beyond

logic.” But the observations are full of intelligence rather than the

platitudes that beset religious enlightenments.

‘Dune’

is heavily steeped in Middle Eastern culture – the precious spice = oil, for

example – and has much commentary on colonialism and exploitation of resources.

Yet whilst sympathetic and respectful of the Fremen natives, it’s a royal

outsider that rallies and guides them. The gender politics are slippery too:

women are concubines and witches, but they also seem to hold formidable behind-the-curtain

power and connivance – they are certainly equal matches for the men, even in

combat. The Bene Gesserit, for example, are a formidable sisterhood of female plotting and power committed

to a breeding programme meant to result in the Kwisatz

Haderach, a calculated Chosen One. Indeed, that they are apparently "influenced by the tales of Maria Sabina and the sacred mushroom cults of Mexico" (says Wiki) shows the rich variety of inspiration that Herbert used. ‘Dune’ touches on too many bases, surely, to be accused

of just one. It’s jammed packed full of weighty ideas and observations.

The guiding point is the apparent “Chosen

One” status of Paul Atreides, the fifteen-year-old heir to the House of Atreides,

trained in arcane ways by his mother and given to visions and reactions from others

that he is Muab D’ib, a religious coming. ‘Dune’ certainly wasn’t the first,

but one can see its popularity and influence as a seminal Chosen One narrative,

even if others overlook its questioning intent. Paul himself is initially reluctant

and disbelieving, although events soon bring out seemingly preternatural

abilities. The Chosen One status drives him directly in conflict with his mother:

he resents her for her part in putting him in that position, the Bene Gesseret breeding

programme. By the finale of the novel in which Paul is given the chance to face

down and outwit all his enemies and rivals, he is giddy with his omnipotence,

even if the last melee is a close call highlighting his mortality. Yet this is

tinged with Paul’s cynicism and self-awareness of his status as myth generator

that defines his character. And as the fulcrum to several Chosen One legends,

this self-awareness and cynicism culminates with his alternating whichever he needs

to best his rivals (Paul Atreides, Muad’Dib, Kwisatz Haderach). Herbert may

have been influenced by Arthurian mythology, but ‘Dune’ is not

fascinated with Romantic Heroism of infallible protagonists. For Herbert, "Dune was

aimed at this whole idea of the infallible leader because my view of history

says that mistakes made by a leader (or made in a leader's name) are amplified

by the numbers who follow without question.”*

It's a grand achievement, the mixture

of hard and soft science-fiction, of convincing ecological and political realities

mixed with futuristic fantasy consistently compelling and intelligent.

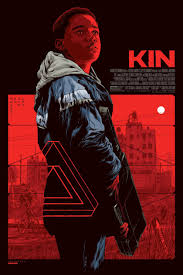

Dune

Director - Denis Villeneuve

Writers - Jon Spaihts (screenplay by),

Denis Villeneuve (screenplay by), Eric Roth (screenplay by)

Stars - Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca

Ferguson, Zendaya

And a serious tone, somewhat humourless, is what Villeneuve

brings, which seems to me thoroughly in keeping with the novel. This is in

inevitable comparison with David Lynch’s madcap adaptation. As Mark Kermode

notes, in Lynch’s version there is always a distraction, so you are never bored

even as it is unravelling before your very consideration. It’s somewhat a highly

enjoyable, compelling misfire where the art design and costumes and effects amaze

even as the narrative flounders in seeking purchase. There’s a lot of amusement

to watch it gleefully pummel onwards, almost-but-not so-bad-it’s- good. Arguably,

the few notes of humour tried for in Villeneuve’s ‘Dune’ stick out like

a sore thumb, but they are fleeting moments – and seemingly all deceptively

crammed in the trailer, which is edited like a Marvel Universe teaser (Action! Quips!).

What I found satisfying in Villenueve’s‘Blade

Runner 2049’ was the subversion of the “I’m The Chosen One” trope. That’s

the very foundation of ‘Dune’,** a primary text for this trope indeed, but

I heard a criticism on the Kermode & Mayo film show where someone found all

the foreboding and premonitions tiresome, but that is at the crux of the narrative,

for it’s all about Paul Atreides being foretold as M’uad Dib. But he is

reluctant, not happy at being manipulated into this prophecy; he’s conscientious

and he is angry at his mother’s apparent manipulations at making him The Chosen

One.

One other major criticism is that he is a White Saviour,

but the character of Paul is a little more complex than that, and certainly

Herbert’s vision is more informed. ‘Dune’ is about colonialism, all

the political power play and wrongful disregard of the natives for the sake of

plundering the resources. Khaldoun Khelil*** is enlightening

on the problems of representation in Villenueve’s adaptation, and certainly in

a post-MCU casting world, the casting could/should have been cannier – and surely

Iannucci’s ‘The Life and Times of David Copperfield’ showed up the shallowness

and inadequacies of the mentality of general casting. Indeed, changing the character

Dr Liet Kynes to a black woman (Sharon Duncan-Brewster) hints at greater

diversity already being an option.

In terms of language, it eloquent in the manner we may

associate with canonical classics, but unlike Lynch’s ‘Dune’ it’s not near-impenetrable.

There’s long exposition narration to begin with, the kind that always raises puts

me dubious, but luckily that is just a stumbling block to the story proper. The

secret sign language between Jessica and Paul is a good visual innovation to

convey the Bene Gesserit training that they share, which is all embodied in the

novel’s prose. Similarly, it does away with voiceovers to replicate the novel’s

articulation of thoughts, the kind of voiceover that Lynch used (which I actually

liked, in retrospect).

Any fan of B I G spaceships will be in Heaven here as

they rise from lakes, block out most of the screen as characters disembark, or

even the ‘thopters resembling dragonflies. It’s a film with scope and scale

with plenty of faultless CGI. There is of course wonderful set design, from the

greenery of Caladan (a sequence more expansive than in the novel) to the spacious

chambers, endless sand banks and tunnels of Arrakis. It’s perhaps not as shocking/suprising

as that of Lynch’s version, but it perhaps feels more organic, more realistic. Surely

many will feel like Jonathan Romney:

“Nowhere

near as enjoyable as Villeneuve’s inspired Blade Runner 2049,

Dune is an achievement for sure, but watching it is rather like having huge

marble monoliths dropped on you for two and a half hours, to the resounding

clang of a Hans Zimmer score.”

Timothée Chalamet is, of course, too old to match the fifteen-year-old

Paul Atreides of the book, but there is a precociousness he exudes, a boyish

maturity if you will that suits the character. Rebecca Ferguson as Lady Jessica

is surely more weepy than in the book, but like the rest of the star-studded

cast, she knows how to play this kind of high theatre. Only Zendaya comes

across as an ill-fit, coming too obviously from the American school of feisty female

acting (but this may be unfair in the long-run).

Lynch’s version is more fun, but Villeneuve wants to

get close to the novel’s sombre tone, and this he does. And perhaps those who

enjoy Lynch’s camp appeal may not enjoy Villeneuve’s sincerity and vice versa.

And of course it’s twice the reward if you go for both, and there are plenty of

us. Villeneuve’s style is of a restrained, underplayed tendency, not typical of

the blockbuster style, more an approach associated with indie. So, whereas there

is all the spectacle you could want, the dramatic conveyance will leave many

cold (certainly, many didn’t engage with ‘Blade Runner 2049’s layers,

thinking it lacked for story). And anyway, ‘Dune’ is not a warm story,

but a tale of calculation and survival in an objective and manipulated design. There’s

something battered about these characters rather than adventure action archetypes.

I came away from Villeneuve’s ‘Dune’ with a sensation

that I had been wowed, and like his ‘Blade Runner’, that it would be on

a second watch that I would truly and fully engage. And of course, this is only

half the story.

· *

Herbert, Frank (1985). "Introduction".

Eye. ISBN 0-425-08398-5.

· ** So to speak. One comment came about ‘Dune’

was that it was his response to Isaac Asimov’s ‘Foundation’ series.

· *** I owe thanks for this link to Derek

Anthony Williams https://www.facebook.com/theneofuturist