Film Summary 2020

home viewing version

And so, film watching became fully a Home Lockdown Sport.

It turned out my annual holiday to FrightFest simply mutated to digital, and I also found Grimmfest this way too. In the end, I “attended” four horror film festivals, missed the London Film Festival and thoroughly intend to go for more digital festivals in the future, hoping they continue this alternative. And of course, there were premiers and such on Netflix and Prime, so even though I thoroughly missed going to the cinema, I still saw some new releases.

Some of these are streaming releases and it's a weighted towards horror, but hey-ho. I bet I am playing a bit fast-and-loose with release dates being 2019-2020 on occasion, but you’ll just have to forgive me.

‘Extraction’ proved popular enough, but superficial. Some good action though.

Won-Tae Lee's ‘The Gangster, The Cop, The Devil’ was the kind of Asian crime thriller that does action and nihilism so well, unmarred by the kind of sentimentality that gave ‘No Tears for The Dead’ hiccups. Here, a couple of gangster movie archetypes join together to stop a serial killer. Stylish and starred ‘Train to Busan’ favourite, Ma Don-Seok.

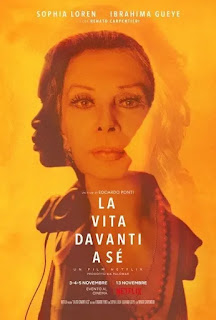

Yes, Edoardo Ponti’s ‘The Life Ahead’ heralded the return of Sophia Loren, but the film belongs to the performance of young Ibrahima Gueye as Momo, the orphan she begrudgingly takes in. Otherwise, it’s a by-the-numbers weepy with not enough grit and/or unpredictability in the detail to make it stand out,

A far more fascinating and troubling sleeper masterpiece was Mong-Hung Chung’s ‘A Sun’ (Yangguang puzhao). It’s about the long-term consequences of crime, hubris, desperation, temper, family ties… all that. It begins with the shocking incident where a man’s hand is chopped off and lands in boiling soup – a moment that wouldn’t disgrace Takashi Miike – and the rest of the film and the subsequent years all lead back to this. There’s the superficial dynamic of the good son and bad son, but both prove enigmas. The father is arrogant and angry and the mother is torn this way and that by all this male conflict. Focusing on the cruelty of life yet the film isn’t mean. It stays non-judgemental with a strong undertow of empathy.

David Fincher’s ‘Mank’ had the formal play expected of him, recreating old school Hollywood with all the modern tricks at his disposal: Dutch Angles, smoke, stylistic nods to ‘Citizen Kane’, etc; look for the cigarette burns, the typewriter title cards, etc. The dialogue plays like sparklers wielded as swordplay – script by Frank Fincher, David’s journalist-essayist father – is fast and clever and very old school: everyone knows just what to say. It’s the kind that you will watch a second time just to listen. It’s pacey in and old school way too, even if it’s length at over two hours is very contemporary. ‘Mank’ isn’t one to turn to for veracity, it seems (say people far more knowledgeable than I), but the general tone of people screwing one other over, the horrendous hierarchy, that all rings true to the stories and reportage I do know. And the subplot about politics and fake news and propaganda is totally contemporary, or at least offers a starting point. It’s all excellent performances and storytelling.

Nick Rowland’s ‘Calm with Horses’ boasted great performances from Cosmo Jarvis and Barry Keoghan and a terrifying turn by Ned Dennehy. An upsetting tale of insidious bullying and manipulation where a local gang uses the gullibility of an ex-boxer for their muscle. It’s concise with truly repellent villains, defiant women, nicely rendered milieu, a sense of a class brutally policing its own, unfairness, and a sudden great car chase. Impressive.

But for a Ladies Only focus, Céline Sciamma’s ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ was sublime. Something of its spaces and moments of quietude reminded me of William Oldroy’s ‘Lady Macbeth’; but this was a different beast, full of warmth and sympathetic elegance. Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel are both captivating, falling for each other over the painting of a portrait. Just a house, some perilous and picturesque cliffs and two smart people falling in love. Sciamma offers some end notes that make this a fully realised tale of fleeting, lost love, but not of regret.

Tayarisha Poe’s ‘Selah and the Spades’ was a nicely played and rendered high school clique conflict drama. The Mean Girls And Guys of High School where the factions all have funky names and are introduced by knowing voiceovers or postmodern techniques is something that I have come to find a turn off, but ‘Selah and the Spades’ is not overdone, has a nice smooth stylish surface. The problem is, having deconstructed Selah, it assumes an acceptance and redemption that the script hasn’t quite worked for. And of course, it depends how you feel about a group of privileged drug pedlars, although there is a lot of nice characterisation.

Similarly, Sophia Takal’s remake of ‘Black Christmas’ just assumed Final Girls triumphing with kick ass and quips was enough to polish up the slasher tropes. There’s some nice setup and it’s decently presented so it’s hard not to think that some of the negativity reaction to it was based in part on garden variety misogyny. But it’s ultimately a little lacking when women reclaiming the genre is storming up a treat and has quickly surpassed gestures of Girls Kick Ass Too! to more sophisticated catharsis.

If you were looking for a really oddball Girl’s Clique At School, Betrand Bonello’s ‘Zombi Child’ provided a fascinating genre mash-up. Part underplayed supernatural – the voodoo Zombi backstory is almost so faint as to be subliminal – and part coming-of-age drama, it’s more magic realism than horror. Probably belongs to that long tradition of bildungsroman streaked with fantasy-horror. But its calm surface is beguiling and eventually asks more than it answers. Best to treat as fable.

But as an example of how feminism has advanced in and has expanded genre, Leigh Whannell’s ‘The Invisible Man’ is a fine text. Rather than remaking the HG Wells tale, Whannel’s screenplay uses the concept to capture the fear and relentless paranoia of an abused woman. He’s always there; you just can’t see him, but she knows. Following the excellent ‘Upgrade’, it’s obvious that Whannell has a fearful respect for technology and its insidious threats: in ‘Upgrade’ and ‘The Invisible Man’, the technology is given plausibility where the effect and use are tied inevitably the individuals flaws and/or villainy. Elisabeth Moss gives a great performance struggling as, of course, no one believes her. Whannell makes the empty spaces in the frame electric with threat.

Similarly, Bea Grants scripts for ‘12 Hour Shift’ and ‘Lucky’ were witty, acerbic, twisty, full-blooded and female-focused/feminist without compromising genre thrills. In recent horror festivals, there’s a lot of this going around, providing fresh paint and venom to genre tropes, but Grant is obviously a reliable voice. Especially with ‘Lucky’, where the analogy takes over and could risk losing credibility, but instead is sad, chilling and fully satisfying.

Likewise, Piotr Ryczko’s ‘I Am Ren’ holds fast to its metaphors and analogies to explicate the female condition. A woman is a faulty domestic android...

Ivo Van Art’s ‘The Columnist’ and Emre Akay’s ‘AV The Hunt’ provided revenge tales for women, the first being satirical on the era of social media trolls, the latter a scathing indictment of patriarchy’s psychopathy. Craig Zobel’s ‘The Hunt’ was a similar woman-kicks-back tale with a upfront class commentary which got it caught in the crosshairs of the zeitgeist and banned for a while. But really it was the kind of enjoyable violent satire that dominates horror festival programmes.

And B. Harrison Smith’s ‘The Special’ provided a gloriously icky commentary on the apparent insatiability of male desire.

There were plenty of noteworthy genre character pieces. One of the best was Jon Stevenson’s ‘Rent-a-Pal’, a sympathetic portrayal of male loneliness leading to desperation and breakdown.

Joe Begos’ ‘VFW’ was a homage to eighties b-movies, which is an overriding trend in the genre at this time. It was far less impressive than Begos’ ‘Bliss’ and somewhat hobbled by a lacklustre female upon which a group of old war veterans leap into one last bought of bloodletting and vindicated violence. But the old timers know what they’re doing. The influence of Carpenter was obvious and the action was delivered decently.

Neasa Hardiman’s ‘Sea Fever’ is the kind of thing that catches my attention more because it tries to do something different with a similar underwater-and-under-siege premise as, say, ‘Underwater’. Surely in a pandemic era, it’s threat of contagion resonates even more. It’s often pretty too.

Jim Cumming’s ‘The Wolf of Snow Hollow’ was another surprising delight, with Cummings himself giving an excellent turn as a small-town police officer trying to simultaneously keep his anger in check and solve a series of brutal killings. Watching him trying to hold it together whilst surrounded by annoyance and lack of competence proved a treat and darkly funny. Your temper may be proportional to the town you’re in. And, of course, anger and Id are the basis of werewolf tales, so all those themes were fully in place. However, anyone expecting a conventional werewolf tale from the title were bound to be disappointed, but it offered a wealth of great characters and turns.

The most unapologetically episodic, free-for all was the glorious oddity and instantaneous cult classic ‘Fried Barry’. Narratively-challenged, the joy was in seeing what and where it and he would go next. Rarely have I been so thoroughly amused and delighted to just be swept along.

There was a handful of horrors that offered different spins on witches. Brett and Drew T. Pierce’s ‘The Wretched’ had some nice witch reveals and a mean streak that made it worthwhile. The supernaturally inflicted amnesia about missing children was a truly creepy and troubling quirk. For something a bit different in the witch department, Aaron B. Kootz’s ‘The Pale Door’ offered an entertaining Western/Horror mash-up with plenty of meat on its character bone and unapologetic in the old-school hook-nose-and-chin witch design. For all the machismo, it was the women here that wielded all the power. ‘Blood Harvest’ offered a more sombre, character-based witch tale that was far better than its title (originally it was ‘The Curse of Audrey Earnshaw’).

Ryan Spindell’s ‘The Mortuary Collection’ was a slickly made horror anthology with a great turn by Clancy Brown, but somewhat undone by an ill-judged final gag.

The fascinating ‘Rose: A Love Story’ by Jennifer Sheridan ended just as it was about to kick into another level. But again, the variation on tropes and concentration on character proved gripping.

I didn’t realise how much I loved Andrew Patterson’s ‘The Vast of Night’ at first: it was such a heady mix of delightful dialogue, mood, the occasional camerawork flourish, and an ultimate sense of unfairness that haunts. I watched it again soon after because I realised it was a favourite for me.

Similarly, I fell in love with ‘Tumbbad’ - directed by Rahi Anil Barve with Adesh Prasad and Anand Gandhi – the more I thought about it.

Johannes Nyholm ‘Koko-di Koko-da’ was yet another that I liked the more I reflected.

Lorcan Finnegan’s ‘Vivarium’ was a total surprise and hit my buttons delightfully. Unfair uncanny absurdist failing reality. That’s the stuff I consider horror just as much as violent killers.

Jessica Hausner’s ‘Little Joe’ definitely won’t be for everyone, but it’s themes of anxiety, commerce and science presented a different kind of invasion. There were obvious foundations of triffids and bodysnatchers, but it was so low-key and insidious, with an overall mannered aesthetic that surely some of its subtleties were lost on many. But it was colourful, intriguing, intelligent and troubling.

For something more conventional, Rob Savage’s virtual séance frightener ‘Host’ proved a breakout horror hit during lockdown. It proved a good jump-scare vehicle, not quite overcoming all the issues posed by live cameras, but very entertaining.

But it was Graham Hughes ‘Death of a Vlogger’ that impressed me more. It perhaps wasn’t the most promising title, but it wasn’t afraid to lets its intelligence and agenda take their time revealing themselves. A vlogger films a haunting in his average flat… In many ways, it was just as twisty as 'I See You'. Starting conventionally enough, it provided me with two unexpected jump-scares and moved into themes of fake news and ambiguity that elevated it with current relevance.

Adam Randall’s ‘I See You’ was an unexpected, excellent thriller treat. It’s one of those that, through a little sleight-of-hand, makes you think you are watching one type of film but… well. The feature that I liked is that the family doesn’t discuss the odd things happening to them because they are in crisis and not really communicating. It’s definitely one to go in with knowing nothing and stick with.

Oz Perkins’ ‘Gretel & Hansel’ was the kind of reimaging of fairy tales inflected with arthouse aesthetic that always fascinates. There was the sense that it wasn’t quite hitting all its marks, was a little unsteady, but Alice Krige’s performance as the witch grounded it all. That, and the production and art design by Jeremy Reed and Leonie Predergast respectively. Matteo Geone’s ‘Pinocchio’ takes a similar approach – a fairy tale given a dose of realism – but far less successfully than his wonderful ‘Tale of Tales’. Perhaps it was the dubbing – okay, definitely the dubbing – but for all its beauty and fascinating oddity, there is something that doesn’t quite gel.

Maximiliano Contenti’s ‘Red Screening’ was a retro-horror with giallo tendencies (it’s a trend), set in a cinema. It’s enjoyable fodder for horror fans, comfort food even, as a small selection of staff and audience fall pray to a killer on the premises. The detail that the director of the film being screened (‘Frankenstein Day of the Beast’) is playing the murderer gives an extra twinge of meta. Aside from a couple of character histrionics, it’s solid fun.

Keola Racela’s ‘Porno’ is, like ‘Red Screening’, also set in the past of a movie theatre. Five employees unleash a succubus which means they will not only have to face the supernatural but their own Faith. You see, they’re all very Christian which gives a fresh tint to genre tropes. It’s this that is most interesting, this limited group struggling with themselves… well, predominantly male angst. After all, the threat is mostly exploding dicks. But it is relatively tame, truly, if and makes only one truly out-there moment of excess and gore amid truly startling (you’ll know it when you see it). The nostalgia isn’t overdone, the cast are game and a step back from outright caricatures. It’s likeable enough, even if it gets a little lost with itself.

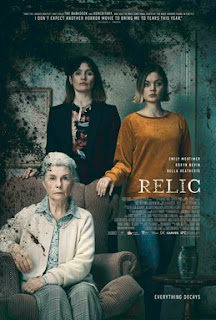

The legendary FrightFest screening of ‘Train to Busan’ will always remain vivid in my memory: the feeling of audience enjoyment was a tangible thing that I can still feel now. The follow up ‘Peninsula’ isn’t as good as that – ‘Train’ was a lightning strike – but it’s still an enjoyable zombie romp, now with a ‘Mad Max’ vibe. The emotional resonance of ‘Train’ kicked so because it was unexpected: ‘Peninsula’ seems to be trying too hard – the superfast zombie onslaught will slow down to let characters emote and the music swell; there’s a lot of performative heart-wrenching – but even so, there’s a lot of fun here.Natalie Erika James’ ‘Relic’, Brandon Cronenberg’s ‘Possessor’ and Remi Weekes’ ‘His House’ were all examples of the genre currently at the top of its game.

Okay, okay, let’s stop there, although I know there are some I've left off.

Well, there’s always the usually daft cries of Death Of Film, but this year the hints of Death of Cinemas seemed closer than ever. It's all the fault of the pandemic, of course. I guess the move to streaming has been even more dramatic than ever. But I also know that ‘Mank’ would have looked gorgeous on the big screen, that I would have been immersed in ‘Possessor’ even more, that I would have loved to see ‘The Vast of Night’ on a big screen (yes, I know it wasn’t a cinema release), that ‘Fried Barry’ would have been delightful with an audience, etc cetera. I think cinema will survive somewhere and somehow, because nothing beats that if you’re a film fan.