Jacques

Tourneur

USA,

1942

Writer:

DeWitt Bodeen

Tourneur’s alternative were-tragedy

is a svelt and elegant tale about how sexuality and jealousy makes one woman

dangerous. Certainly, Irena is quite charming, sweet, smart and endearing at

first – Simone Simon barely seems capable of raising her voice – and that means

she is appealing intellectually and disarming. And she’s a Serbian immigrant

and therefore exotic, so it’s easy to see how a decent enough all American chap

might fall for her. She has a warmth and vulnerability that commands empathy

throughout. But this foreignness also comes with troubled ancestry and a

delusion that, when this exotic sexuality is tapped, she’ll become a lethal

panther. This becomes a problem when she senses her husband falling for

another.

But there’s nothing mean to our

central love-triangle: there’s a definite maturity to DeWitt Bodeen’s

screenplay. When Oliver Reed (Kent Smith) must tell Irena that he’s fallen for

someone else, he doesn’t blame Irena for being difficult or stringing him

along, but it’s with regret and acceptance of responsibility. Also, Alice (Jane

Randolph) isn’t some love rival drawn bad, but often suggesting the more

sympathetic actions when dealing with Irena. Moira Wallace writes that “Simone

Simon seems by nature to be more kitten than were-wolf”, but that is surely the

point, that Irena isn’t a siren seductress, a femme fatale to anyone but

herself. After all, “She never lied to us.”

It’s a text wholly built from fear and

phobia, from a woman’s fear of her ancestry and sexuality, and of her loneliness

and her place in social convention. Undoubtedly also due to budgetary constraints,

it nevertheless evokes the eerie and uncanny with a success that a film with

more resources probably would not have achieved. Secondarily, it’s the male

fear that a woman’s troubled sexuality can’t be trusted, perhaps especially if

it’s foreign and exotic. And there is also the hint of lesbianism, not least

when a stranger calls Irena “Sister”. It’s also notable that it’s Alice that

first believes in the threat and powers of Irena, without much hesitation when

she’s confronted by weirdness, while the men mostly patronise, disbelieve and

consign Irena to insanity. The men can’t quite see pass their own agendas, and

in Dr Judd (Tom Conway), his assumption that his privilege and gender trump all

is a wrongheaded arrogance. There are forces at play here that the very

straight characters outside Irena are barely aware of.

The film’s major laziness is in

suggesting some makeshift cross and Christian declaration might fend off

something so primal, as if the film thought it was a somewhat more traditional supernatural

monster movie fighting off a pagan threat (and although this can be attributed

to Oliver’s beliefs, the film does seem to play along). But the bus moment is

one of the genre’s great jump-scares, and there is something truly primal and

fearsome in the similarly iconic swimming pool set piece. Rob Aldam writes,

“Largely

overshadowed by Paul Schrader’s inferior remake, The Cat People is a milestone

in horror movies. The way Lewton and Tourneur use shadow in lieu of an actual

monster completely revolutionised how films are made. There’s so much more

malice in a fleetingly glimpsed silhouette than revealing all your cards to the

audience.”

The use of shadows and light are

exemplary throughout, shadows becoming bars and obscuring the monster and monstrous

so it is always lurking and pending. Tourneur and cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca

worked on film noir before and put the chiaroscuro to the best evocative use for

horror. ‘Cat People’ successfully conjures the uncanny and abstract anxiety,

those elements that touch the everyday, perpetual engine of the genre. The monster revealed is our own fear of

ourselves. It’s certainly a text for those who feel like outsiders, even

surrounded by decent, sympathising people.

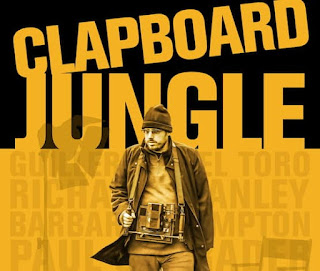

Paul

Schrader

1982

– USA-Japan

Screenplay: Alan Ormsby

Paul Schrader doesn’t think of this

as a remake of the Jacques Tourneur classic, which he doesn’t seem to rate, and

seems to think the inclusion of a mysterious lady saying “My sister!” is his

homage to the original; but it riffs on the swimming pool scene and the famous

bus jump-shock and in that way follows similar beats to the original.

Schrader’s take is very different and earns that contentious label as a

“re-imagining”, but to reject it as a remake is surely a little disingenuous.

What it does do, like Cronenberg’s

‘The Fly’ and Carpenter’s ‘The Thing’, is to take a beloved source

material and update it successfully, bringing what was all allusion and

suppression in the originals to the surface. For ‘Cat People’, that

means all the kink and sleaze and dodgy sexuality is front and foremost. And

surely Natasja Kinski nude was a selling point, although this was also in

McDowell’s nude period. Oh, and to add incest too. Kinski’s offbeat sexual

appeal where she goes from innocent to seductress when discovering she turns

into a panther when primal urges are released by sex certainly centres the

film. She hangs between Malcolm MacDowell’s sleazy incestuous perversity and John

Heard’s wholesome All American machismo.

This was slightly side-stepped in the

shape-changing cluster including ‘An American Werewolf in London’, ‘The

Howling’ and ‘The Thing’, perhaps because it wasn’t funny or

satirical or outlandish, but I always put them in the same pot. The highpoints

are McDowell’s creepy leaping on the end of a bed, the arm being pulled off,

the unforgettable desert scenes and Giorgio Moroder’s quintessentially Eighties

pulsing synth-score: I even think of the orange tint to the dream-desert sequences

as an Eighties orange. The score is one I have listened to ever since. Its

weaknesses are a couple of moments with female victims that wouldn’t sound out

of place in ‘The Man With Two Brains’, and the iconic pool scene that,

here, seems to imply that Irena can transform at will, which isn’t in the rules

of this version.

The sexuality in ‘Cat People’ walks

a line between arthouse and exploitation and its actual standpoint a little

hard to pin down. Sexuality is primal, unleashes the beast and perversion: even

the ostensibly nice and normal sex between Irena and Paul leads to bondage. Based

on this, Gary Arnold calls a Schrader “an exploitation director with delusions

of grandeur”, but that seems pretty self-evident,

and hitting that sweet spot between conceived “high” and “low” art is genre

privilege. ‘Cat People’ is a near-miss, but still intriguing.

The ending signals tragedy, and it is

conceptually better than the run-of-the-mill monster movie ending that Schrader

talks of, but it also symbolises a woman’s sexuality being caged up by a man

for her own good, and by her own choice. There’s an uneasy murkiness here, but

the elements of arthouse and exploitation tame one another to produce something

that is quite unique, and certainly beguiling, despite and because of its crude edges and pulsating Eightiesness.