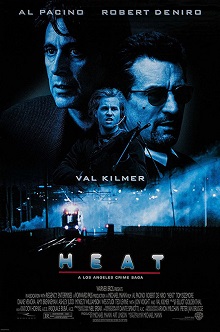

Michael

Mann, 1995, USA

It’s

slick and moody, swinging between a tinge of blue filters and bright city sun.

There are many impressive set pieces, not least the opening robbery and a

central shoot-out. This is why Mann is revered and rightly so. Surely the trend

of a lot of Eighties thriller gloss can be credited to him: I remember ‘Miami Vice’ being very influential. He

is not style-over-substance, but there’s a shallowness to his focus on troubled

men.

But

here’s what stops me from fully investing. The thriller elements are great but

the boys’ criminality stuff often unintentionally funny when they’re being

macho angst-ridden, which is a trait that defines much of Mann’s work. It’s half

hour in and the manly tantrums and posturing begin and Pacino starts barking;

it gets so they can’t walk into a room without throwing or slapping props. “I have to hold onto my angst!” Pacino says. Mostly,

male relationships are defined by pissing-contests and one-upmanship.* The much

touted coffee scene with Pacino and De Niro is of course well played but they

talk about family and dreams, which is pretty standard for this kind of thing,

and they just come short of saying “Hey, we’re different sides of the same

coin, aren’t we?”

There’s

a lot of bullying of pretty women and a serial killer thrown in to no

discernible effect other than making a repellent character even more so. All

the women are defined by their men and are sympathetic to their faults; all the

men are so wedded to their own vision of themselves that it crowds out any

definitive space for the women. Indeed, should the women challenge this, the

men respond with violence and temper-tantrums. It's like one of those Eighties "adult" moody ballads - the kind that bring so much atmosphere to Mann's films - where men are idealising some romance where the woman got off her pedestal, but the man still blames her beauty. It’s been this way since Mann’s 1981’s

‘Thief’ at least, and there is a

sense that we are meant to find the men tragic and poignant for this. But it’s

more like Mann’s protagonists are mostly assholes and the female actors giving

their roles far more soul and complexity than they perhaps warrant; far more convincingly

than the men (in this case headed by Diane Venora, Amy Brenneman and Ashley Judd). It’s the women that sacrifice themselves to the men’s obsessions

and unwillingness to change.

It’s a sense that this all a boy’s game that keeps

me from taking it all fully seriously: Mann’s films never quite call the men on

their assholishness and the idea that they aren’t actually the tragic martyrs to machismo they would like to imagine themselves to be doesn’t seem an option as their overriding masculinity is the narrative ley lines. It’s this that keeps me at a distance, even as

I’m admiring the mood and artistry.

·

Compare with Alan Clarke’s ‘The Firm’ where the

men can’t see past petty rivalries and insulting one another; or the wry humour of Sergio Leone's Spaghetti Western showdowns.

2 comments:

My favourite relationship in that film is between Dennis Haysbert's getaway driver,and his wife,Kim Staunton.Their screen time is brief,but there's that one devastating scene where he's finding it hard to go straight,and she's trying to encourage him-slays me every time.Of course it fits into your theory,but there's an honesty there I think.

And he's not an asshole. It's a good moment because his subplot shows how demeaning and humiliating low paid work is no incentive for anyone, and an impetus for crime. Unlike the other men, seems to be working *with* her at life, not at odds to prove his masculinity. Hmm, I would argue he is where the true tragedy lies. But he's just a side story that only helps to show up the assholishness of the others.

Post a Comment